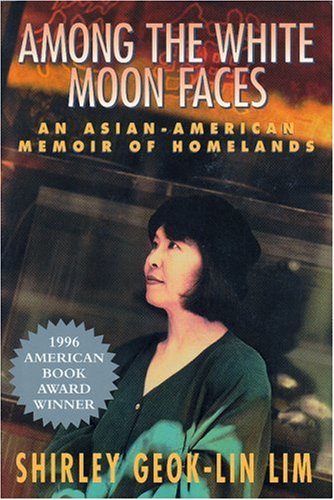

Among the White Moon Faces:

An Asian-American Memoir of Homelands

“The first time I heard Shakespeare quoted, it was as a joke,” writes poet and Asian American scholar Shirley Geok-Lin Lim in the introduction to her American Book Award-winning memoir, Among the White Moon Faces. Before she’d ever read the play, Lim took the word “Romeo” – as spoken by Malaysians – to mean a sort of “male effect,” a sexualized, Westernized code word for “the kind of thing men did to women.” “This was Shakespeare in my tropics, and romantic love, and the English language: mashed and chewed, then served up in a pattering patois which was our very own. Our very own confusion.” In many ways, Among the White Moon Faces is the chronicle of just this sort of confusion: linguistic, cultural, and sexual. The child of a Chinese father and a peranakan, or assimilated Malaysian Chinese mother, Lim grew up with a tangle of names, tongues, and identities: Lim Geok-Lin, to signify her position in her grandfather’s lineage; Shirley, after her father’s fascination with the American child-star Shirley Temple. As a girl, Lim refuses to speak the Hokkien dialect of her father’s Chinese family, prefers the Malay spoken by her mother’s relatives, and eventually winds up speaking almost exclusively English. Years later, as a visiting professor in Penang, she finds herself teaching in English, her language of fluency, while an Australian colleague leads his classes in Bahasa Malay and asks her advice in translating American idioms.

These cross-cultural ironies echo throughout Lim’s thoughtful, politically astute memoir, which covers ground ranging from the neglect and hunger of her Malaysian childhood, to her Anglophile education, to the loneliness of her first years in America. As a Chinese Malaysian, she faced discrimination not only from the colonial British, but later, after independence, from ethnic Malays as well. Reared in an expatriate culture, Lim was doubly dislocated by immigrating to America. Here, too, Lim encountered prejudice, as an Asian female, as a poet, and as a brown-skinned, British-accented anomaly who fit no one’s notion of who she should be. In the end, Lim finds a kind of balance in her perpetual exile, using sisterhood and the solace of writing to create a sense of place – and to counter the pull of ancient ghosts. “Listening, and telling my own stories, I am moving home,” she writes. —Mary Park

Purchase

Citation Information

- Publisher: Feminist Press

- Publication Date: 1997